As the TFELT report discusses, a growing body of research provides support for the value of self-reflection aimed at improved teaching performance in higher education as well as the K-12 context (Kirpalani, 2017). Specifically, self-reflection enables educators to exercise agency in their own professional knowledge and development.

For this reason, beginning in Spring 2024 the University of Missouri requires the completion of an annual self-reflection on teaching from every educator participating in the annual review process, using a framework developed by TFELT.

Completing and Submitting the Self-Reflection for Annual Review

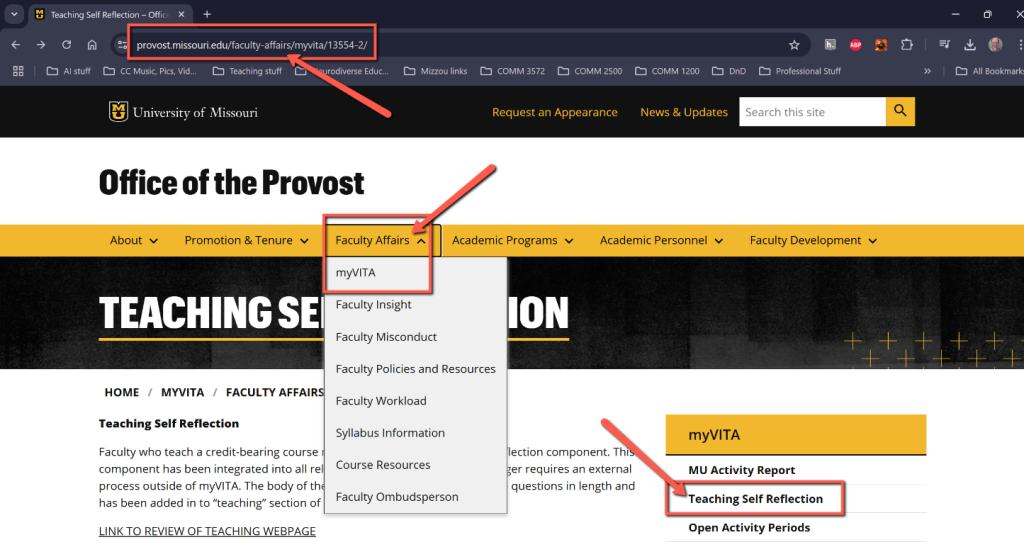

The Annual Teaching Self Reflection will be submitted as part of the annual review self-report on the myVITA platform.

To complete the annual Teaching Self Reflection process successfully, faculty should follow these steps, in order:

Step 1: Create a document file (e.g., Word, Google Doc, etc.) to draft and save your answers to the Teaching Self Reflection prompts. You will want to create a separate copy of your answers rather than completing them in the myVITA self-evaluation report directly, for two reasons:

- to maintain a personal record of your annual Self Reflection that can be used for ongoing teaching reflection in preparation for tenure and/or promotion reviews, future course development or revision, and

- to enable revision of some prompt responses (e.g. course learning objectives) to simplify the Self Reflection process for subsequent annual reviews.

Step 2: Read over the prompts and decide on two points for the Teaching Self Reflection:

- One (1) course taught over the past calendar year that will be the focus of this year’s Self Reflection.

You may select any course in your teaching load that you like. It could be one that is your primary teaching responsibility. Alternatively, it could be a course that you teach less frequently, a newly developed course, or a course that provides challenges that you would like to address.

When choosing, consider how intentional reflection on that course might help you continue to improve it and/or your teaching work in general. For subsequent annual reviews you might select different courses as the focus for self reflection, or select the same course and consider different aspects of it that are useful to examine. - One (1) of the four Dimensions of Teaching for Learning Effectiveness that will be the focus of the relevant prompt in the Self Reflection.

Explanations for all four Dimensions are available on this Review of Teaching website. While you may select a Dimension that you believe is pursued successfully in your chosen course, consider selecting a Dimension that poses challenges for your teaching in your chosen course, or that perhaps you haven’t yet pursued regarding that course. Remember, the ultimate purpose of the Teaching Self Reflection is intentional and thoughtful professional development for growth and improvement in teaching.

Step 3: Reflecting especially on the course you have selected, write responses to the following prompts:

- Course I am reflecting on. If you do not have a course to reflect on, describe your instructional context.

Here, “your instructional context” refers to your teaching-related responsibilities that do not involve a specific course. If you are evaluated by your academic unit for teaching but do not actually teach specific courses, you can elect to reflect on such teaching activities as conducting student workshops, clinical supervisions, or peer professional development sessions.

Step 3: Reflecting especially on the course you have selected, write responses to the following prompts:

- Student Feedback: Please note that your student feedback scores are displayed in each of the 5 data constructs, which are “Collaborative”, “Supportive”, Structured”, “Cognitive Engagement”, and “Teaching for Learning Effectiveness”. Use the space below to contextualize your student feedback data. See the Review of Teaching webpage (linked at top of this form) for additional guidance.

This prompt provides you with an opportunity to construct a brief narrative interpretation of your student feedback results. Your explanation for why you received the results you did, making sense of strength and challenge areas based on relevant variables, can help your department chair or other faculty evaluators assess the data within a broader context. Such variables to consider in your interpretation can include (but are not limited to):

- Observations made during the course (e.g., student dynamics, classroom climate, student experiences with specific activities or assessments, self-observation of teaching practices, etc.)

- Level of personal teaching experience

- Experience teaching specific courses

- Course characteristics (e.g., undergraduate or graduate, in-person or online, large- or small-enrollment, for majors or for general education, required or elective, etc.)

- Student characteristics (e.g., undergraduate or graduate, majors or non-majors, level of academic experience in the discipline, etc.)

- Disciplinary or subject-matter characteristics (e.g., limited prior student exposure, unique challenges or difficulties, student misperceptions, etc.)

- Unique external factors that might influence student responses (e.g., time of course meetings, teaching space, external environmental or social conditions that might impact student engagement, personal life circumstances that might impact teaching practice, etc.)

Step 3: Reflecting especially on the course you have selected, write responses to the following prompts:

- Learning Environments: Effective educators use student-centered instruction to create learning environments so that all learners can be successful. Thinking about your class and the resources in the description, in what specific ways are you fostering or developing student-centered learning environments so that all learners can be successful?

Reflecting on this prompt involves considering teaching for “student-centered learning.” While this concept has been defined and described a number of ways, it is perhaps best understood in terms of student agency, which involves “student capabilities to influence their learning environments” (Klemenčič, 2017, p. 80).

According to Klemenčič (2017), at least two conditions are necessary for students to exercise agency in their learning. The first condition is a sense of autonomy within which students perceive the freedom to be themselves and pursue opportunities regarding their learning. The second is a learner mindset that includes self-efficacy (i.e., the learner believes they can act to have a positive effect on their learning) and self-regulation (i.e., the learner’s ability to make conscious decisions regarding their learning).

The successful development of student agency involves learning environments that foster the student’s autonomy and growth mindset for learning. So, when reflecting on this prompt, you might consider the ways in which your teaching foster a sense of agency for all of your students – or, of course, areas in your teaching practice where you might pursue development to improve.

Student-centered learning environments include (but are not limited to) conditions such as:

- A positive, supportive climate in which all students believe they belong and can learn;

- Teaching that recognizes and builds upon “where each student is at” with regard to students’ unique knowledge, experiences, and perspectives;

- Instructor-student and peer-to-peer interactions that are respectful and provide opportunities for all students to have input in their learning;

- Providing instructional supports that enable all students to access learning opportunities and achieve success on learning objectives.

For more information on student agency and student-centered teaching for learning, click here for a report from the National Center for the Improvement of Educational Assessment (Brandt, 2024).

Step 3: Reflecting especially on the course you have selected, write responses to the following prompts:

- Course Learning Objectives: For the course(s) you have selected to reflect upon, please list your Course Learning Objectives and reflect on how your learning activities and assessments align with up to three of these objectives.

This prompt requires you to first identify the Course Learning Objectives (CLOs) for the course you have identified to reflect upon this year.

Then, for each CLO, you should discuss at least two things:

- First, the assessments you use to determine if a student has achieved the CLO. “Assessments” are the primary summative evaluation activities that determine the bulk of a student’s course grade. These usually include exams and high-stakes quizzes, essays, oral presentations, and other significant projects or evaluative activities that are relevant to your discipline (e.g., multimedia presentations, creative works, clinical or lab practicals, etc.).

You will want to discuss the extent to which your current assessments align with your CLOs; that is, you want to answer the questions, “Are my assessments actually designed to demonstrate student learning that is relevant to my objectives?” and “Am I requiring or evaluating elements of student work that are not actually directly related to my objectives?” - Second, the learning activities you implement so that students can complete and succeed at the course assessments you require. Alignment on this level is about answering the question, “Have my students been provided learning resources and practice opportunities that will prepare students to successfully complete the required assessments?”

Learning activities require student engagement with a wide variety of relevant materials and opportunities, such as (but not limited to): course readings, instructional audio or video recordings, class discussions, small group exercises, early drafts of later assessments, practice problems and other low-stakes opportunities to apply course concepts, etc.

In addition, you might take your reflection further, beyond mere course alignment to evaluate your implementation of course assessments and activities – which approaches seem to be working, and which might require some adjustment, revision or replacement.

Alignment of Course Learning Objectives, assessments and learning activities is often discussed as the central principle of “backward course design.” To learn more about backward design and alignment of learning objectives, assessments and learning activities, check out this resource from the Center for Teaching at Vanderbilt University.

Step 3: Reflecting especially on the course you have selected, write responses to the following prompts:

- Dimensions of Teaching for Learning Effectiveness: The University of Missouri identifies four Dimensions of Effective Teaching:

1. Welcoming and Collaborative

2. Empowering and Supportive

3. Structured and Intentional

4. Relevant and Engaging

Please select one of the four dimensions to reflect on for this past year of teaching. Consider how your current teaching involves this dimension and how you might explore it further. For more information on each Dimension, including specific elements of each that can provide ideas for reflection, please reference the links available in the top instruction form section.

Use the links above to find explanations and examples for each of the four Dimensions. Select just one (1) of the four as the basis for your response and reflect on how your teaching in the course you have selected for the Teaching Self Reflection addresses this Dimension.

While this prompt might be answered in a variety of ways, consider using a structure like this to guide your response:

- Describe how 1 to 3 aspects of your course design, instruction, and/or assessment strategies in the course are intended to address the outcomes suggested by the Dimension.

- Reflect on whether and how each of these teaching aspects succeeds in addressing the Dimension. Remember, discussing elements of your teaching that do not work as successfully as you expect is part of effective reflection, and can be even more important for your professional development than discussing areas of strength and success. Discussing both strengths and challenges will be useful to you as you continue to grow and improve in your teaching work.

Alternatively, if you believe that your teaching approach for the course you have selected does not yet address the Dimension you selected, you may reflect on and discuss why that might be the case and what future actions (if any) you might take to develop your course and/or your teaching in this area.

Consult the myVITA page on the Provost’s website to confirm how to access and submit the Annual Teaching Self Reflection on myVITA.

The Teaching Self Reflection component of the annual review process should be completed as part of the myVITA self-evaluation form, located in the “Teaching” section. The precise location may vary depending on the format of the self-evaluation form required by your academic unit.

Once you have located the Teaching Self Reflection section in your self-evaluation form, copy and paste your responses to the five prompts in the appropriate form fields.

Why Write a Teaching Reflection?

The Task Force to Enhance Learning and Teaching (TFELT) observed in their June 2021 report that “reflecting on one’s classroom and pedagogy is a cornerstone of learner-centered teaching (Blumberg, 2016), and is thus essential in ensuring effective teaching.”

The importance of teaching reflections dates to educational philosopher John Dewey (1933) who defined “reflection” as:

the active, persistent and careful consideration of any belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the grounds that support it (p. 9).

Schön’s influential The Reflective Practitioner (1983) examines “reflection-in-action” – the cognitive process of making sense of an experience as it happens – and “reflection-on-action” – a retrospective examination of an experience to make sense of choices and actions –as primary means for professionals to learn from their experiences. Blumberg (2016) describes the process articulated by Dewey and Schön as “an action– reflection–action cycle” (p. 90).

When it comes to teaching in higher education, Ashwin, et al. (2015) provide a compelling argument for understanding effective teaching for learning as the product of reflective practice that involves regular questioning of our assumptions regarding our identity, teaching contexts and practices. They explain how such self-examination of teaching practice relies both on discovering and making use of evidence and on engaging in dialogue with local colleagues and even public audiences. In doing so, we might avoid important inconsistencies between the teaching philosophy we espouse and our actual teaching behaviors (Blumberg, 2016).

Whether applied to our classrooms, labs, studios and clinics, a reflection on our teaching asks us to carefully consider the beliefs and assumptions behind our choices and actions with teaching, including our approaches to designing our courses and assignments, how we relate to our students, and how we assess student learning. We can do so in the moment as we teach and, importantly, can incorporate regular reflection on our teaching with the benefit of hindsight to consider successes, challenges and potential alternative approaches.

While self-reflection on teaching can initially seem daunting, ultimately the activity boils down to discovering answers to three basic questions offered by Weimer (2010):

- Who am I (as a teacher)?

- What do I do (as a teacher)?

- Why do I do what I do when I teach?

Universities across the nation ask faculty to complete annual teaching reflections. These reflections can take many forms: from informal reflections used for formative assessment of teaching on the one hand, to formal reflections used for summative assessment of teaching where they count toward contract renewal and annual promotion and tenure processes, on the other.

Regardless of format, an annual commitment to teaching reflections signals a university’s dedication to effective teaching to students, educators, and the university culture.

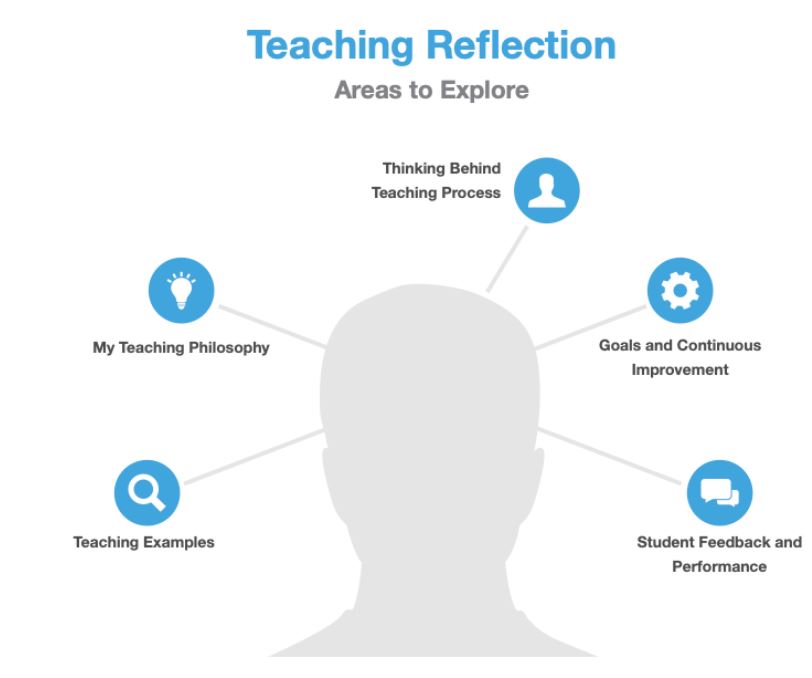

Teaching reflection provides opportunities to grow in your teaching and evolve your teaching practices over time in sync with the ever-changing student body. Among other benefits, a teaching reflection enables you to:

- Explain your teaching philosophy

- Explain your reasoning for teaching choices

- Describe the thinking-process behind teaching decisions, both in structure and in-class

- Provide key examples of teaching approaches

- Contextualize student feedback and performance

- Identify areas for improvement, next steps, and goals

- Identify your needs as an educator

Assessing the Self-Reflection in an Annual Review

The contents of the teaching self-reflection submitted on myVITA will be examined by the educator’s chair and/or others responsible for annual review decisions on the department level. TFELT’s recommendations in this area emphasize the importance of assessing these self-reflections in a manner that fosters a growth mindset for the educator and encourages candid self-disclosure regarding areas of challenge in teaching as well as areas of strength in teaching. The most important function of teaching self-reflection is to facilitate an intentional and honest examination of one’s professional practice, as well as goal-setting and establishing plans to address areas of challenge for improvement and innovation in teaching.

In order for the annual teaching self-reflection to facilitate such professional growth and development, an educator’s self-disclosure of personal or professional challenges in teaching should not be used against them by department reviewers as evidence of “ineffective teaching.”

The statements and artifact evidence in the self-reflection will not be made part of subsequent promotion and tenure materials presented by the department to the college and university, unless the faculty member chooses to provide them as part of their evidence of teaching effectiveness. Department chairs will, however, be asked to indicate to college and university reviewers whether annual teaching self-reflections have been completed appropriately by the tenure or promotion candidate.

Resources for Effective Self-Reflection on Teaching

The MU Teaching for Learning Center has created a mini-course on Canvas to assist educators on campus to understand and complete the annual teaching self-reflection more effectively.

Besides explaining how to complete the TFELT self-reflection, this mini-course provides additional insights on important elements of teaching for learning integrated into the self-reflection. These include:

- constructing effective learning objectives

- aligning course assessments and activities to learning objectives

- practicing Teaching for Learning Effectiveness principles.

This mini-course is one in a series developed to help members of the campus community better understand and use TFELT’s recommendations for teaching evaluation.

Additional resources in this area may be found on the “Resources” page of this website.

References:

Ashwin, P., Boud, D., Calkins, S., Coate, K., Hallett, F., Light, G., Luckett, K., MacLaren, I., Martensson, K., McArthur, J., McCune, V., McLean, M. & Tooher, M. (2020). Reflective teaching in higher education (2nd Ed.). Bloomsbury Academic.

Blumberg, P. (2016). How critical reflection benefits faculty as they implement learner-centered teaching. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 144, 87-97. DOI: 10.1002/tl.20165

Brandt, W.C. (2024). Measuring student success skills: A review of the literature on student agency. National Center for the Improvement of Educational Assessment. https://ibo.org/globalassets/new-structure/research/pdfs/student-agency-final-report.pdf

Dewey, J. (1933; 1910). How we think. Buffalo, New York: Prometheus Books.

Kirpalani, N. (2017). Developing self-reflective practices to improve teaching effectiveness. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice, 17(8), 73-80.

Klemenčič, M. (2017). From student engagement to student agency: Conceptual considerations of European policies on student-centered learning in higher education. Higher Education Policy, 30, 69-85. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41307-016-0034-4

Schön, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Jossey‐Bass.

Weimer, M. 2010. Inspired college teaching. Jossey-Bass.